On the Relationship of Structure to Detail

Sometimes you find a thought sloshing around the back of your mind in an intriguing but unfocused way for quite a while, when suddenly you come across something that brings it sharply into focus. I’ve had a couple of these recently, both sparked by the same stimulus.

Towards the end of last year I read Donald Weed’s What You Think is What You Get, in which he makes a distinction between axial and appendicular functions in the skeleton, and, consequently, between postural and gestural dimensions of bodily use. This is in itself a useful concept to have to hand when learning motor skills. It is very easy to put all our attention on the bits that are specific to the task in hand ( e.g. conducting, playing piano, chopping onions, to take examples from my own life), whereas the success of these specialist, gestural movements is to a significant extent dependent upon how well we are managing the general, postural use of the self.

But something about the way he wrote about these ideas got me imagining these bodily relationships as a metaphor for the relationship between structure and ornament in music. The detailed, surface-level features that give individual pieces of music their specific identity are held together and organised by larger-scale structural processes that are more generally shared by pieces belonging a given idiom.

This metaphor appealed because I spend a lot my time thinking about both musical narrative and the physical acts required bring it to life. Like my metaphor of a central ‘furnace’ as starting point for breath, emotion, and movement with Women in Black, a metaphor that maps text and act onto each other offers a sense of connection as well as cognitive efficiency. And it allows the attention to shunt between levels at both ends of the metaphor: the nuances in the fingertips, or the fundamental legato implicit in the poise of the head.

But, you know, it was just a metaphor, there wasn’t any obvious actual connection between the two domains, other than structural homology. It remained a pleasing way to think about the Real and the Ideal of one’s praxis at the same time, but didn’t seem to have any mileage beyond the imaginative.

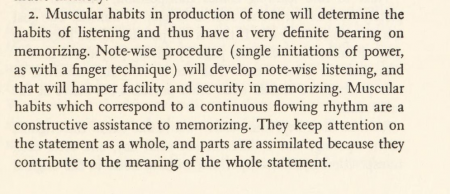

And then I read Abby Whiteside’s Indispensables in Piano Playing, which posits a directly causal relationship between physical and musical structures, mediated by how we listen to the music we are producing. The idea runs through the whole book; the following passage from the section on memorisation presents possibly the most succinct expression of it (p. 61):

The upper arm’s role in both guiding horizontal movement around the keyboard and provision of power to depress the keys is thus directly equated with longer-range structural processes, which should in Whiteside’s concept generate and guide the details of passagework audible at the fingertips. The book as a whole presents a polemic against a technique that focuses on primarily on what the fingers are doing, on the basis that not only does that make everything much harder work for the pianist, but it also fragments the music and destroys its longer-range sweep and direction.

Note also the elision of how you listen to yourself and how you think about music: note-wise listening prevents the perception of longer-range musical narrative. And note-wise listening is fostered by note-wise playing: the conceptual model emerges from embodied experience in the world.

So that was the first hitherto vague thought that Abby Whiteside brought into focus for me. I think I’ll come back to the second in a different post, otherwise it will all start to get rather long and indigestible.

...found this helpful?

I provide this content free of charge, because I like to be helpful. If you have found it useful, you may wish to make a donation to the causes I support to say thank you.

Archive by date

- 2024 (17 posts)

- 2023 (51 posts)

- 2022 (51 posts)

- 2021 (58 posts)

- 2020 (80 posts)

- 2019 (63 posts)

- 2018 (76 posts)

- 2017 (84 posts)

- 2016 (85 posts)

- 2015 (88 posts)

- 2014 (92 posts)

- 2013 (97 posts)

- 2012 (127 posts)

- 2011 (120 posts)

- 2010 (117 posts)

- 2009 (154 posts)

- 2008 (10 posts)